Lucy McKenzie

Prime Suspect

Museum Brandhorst

10 September 2020 - 21 February 2021

Contents

- Introduction

- Video - Lucy McKenzie in conversation with curator, Jacob Proctor

- Installation views

- Essay - Ars Technica by Jacob Proctor

- Downloads - Further suggested reading

Developed in close collaboration with the artist herself, and featuring over 100 works dating from 1997 to the present, the exhibition will for the first time examine the full scope of her oeuvre. It brings together examples from all of the artist’s significant bodies of work, including early paintings relating to pop music and Cold War-era Olympic games; her subsequent engagement with the traditions of Scottish and Eastern European muralism and Belgian illustration; and large-scale paintings based on historic architectural styles. Also included are the collaborative fashion label and research bureau Atelier E.B.; recent works blurring the lines between painting, sculpture, and furniture; as well as new works commissioned especially for the exhibition.

For more than twenty years, Lucy McKenzie has excavated and transformed images, objects, and motifs from an almost impossibly broad range of historical moments and contexts in the histories of art, architecture, and design; literature, music, and film; fashion, politics, and sport. Beginning in 2008, she has practiced the tradition of trompe I'oeil painting, using it as a means to inhabit, critique, and reimagine earlier eras of art and design; illuminating an alternative history of modern art in which the so-called applied arts emerge as essential actors in a narrative that diverges from the established chronologies of modernism and the avant-garde. Despite her impressive skills as a painter—present from the start but honed by the unusual decision, after several years of success on the international stage, to complete a rigorous course of study in nineteenth-century decorative painting techniques—McKenzie has consistently refused to privilege one form of visual or material production over another. Intentionally or not, this has led her on an idiosyncratic path emphasizing vernacular and collaborative practices long marginalized or denigrated in the context of the fine arts. Her embrace of what she calls "procedural" painting is part and parcel with an approach that treats the medium less as an autonomous art than as a technology, one that is deeply imbricated in the same commercial, industrial, and cultural systems as photography or music.

Excerpt from Jacob Protor's essay, Ars Technica, which is published in the catalogue accompanying the exhibition (I.S.B.N. 9783960988526). The essay can be read in full at the bottom of this page or by clicking here.

On September 12th, Lucy McKenzie discussed her oeuvre with curator Jacob Proctor and provided insights into her work. You can view this talk in the YouTube video below.

Below the video you will find installation views from Museum Brandhorst, each as a slideshow accompanied by archival images of each work's prior presentations and context.

Installation views

Lucy McKenzie

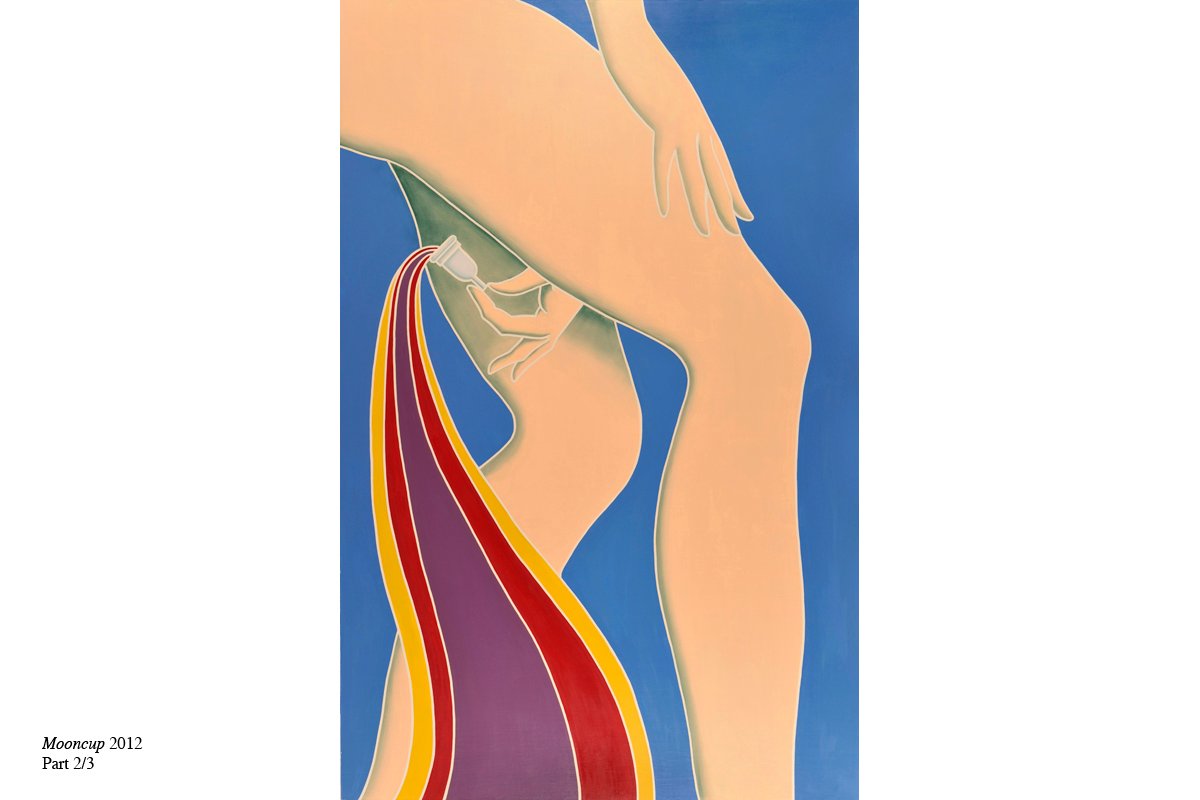

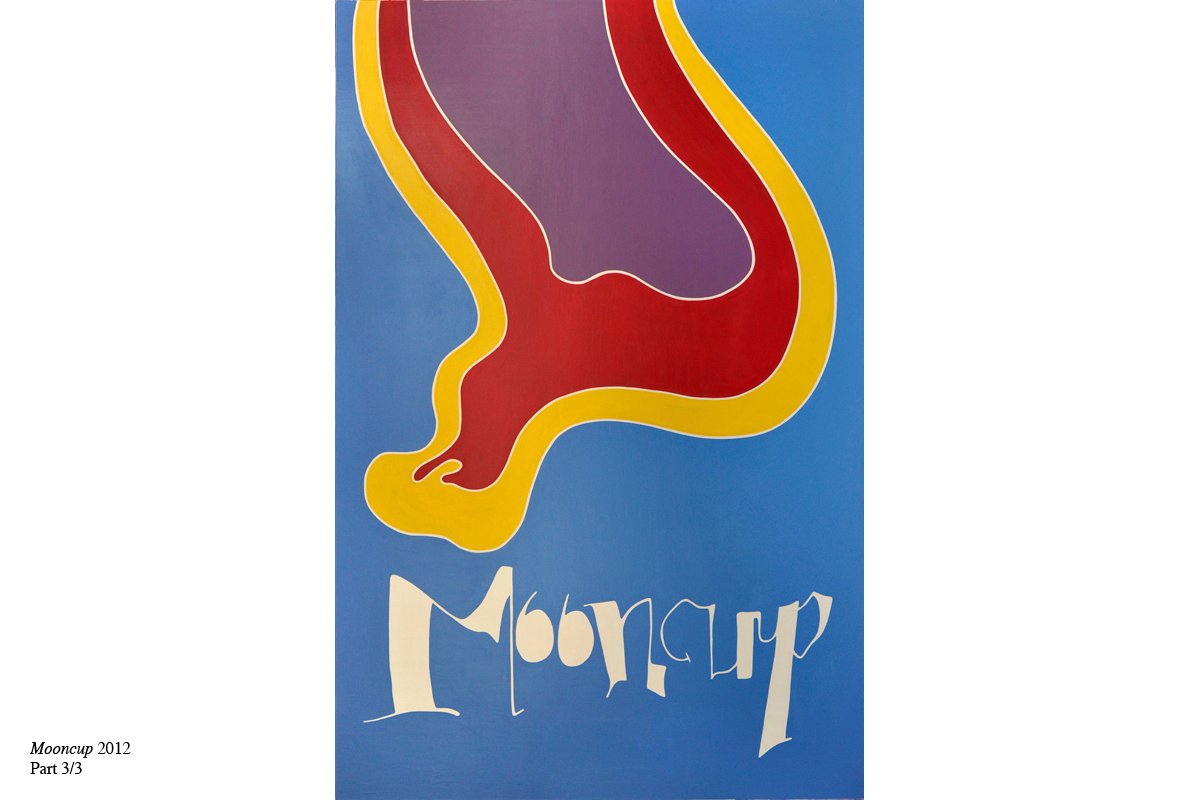

Mooncup

2012

Acrylic on canvas

3 parts, 400 x 260 x 4.5 cm / 157.5 x 102.4 x 1.8 in each

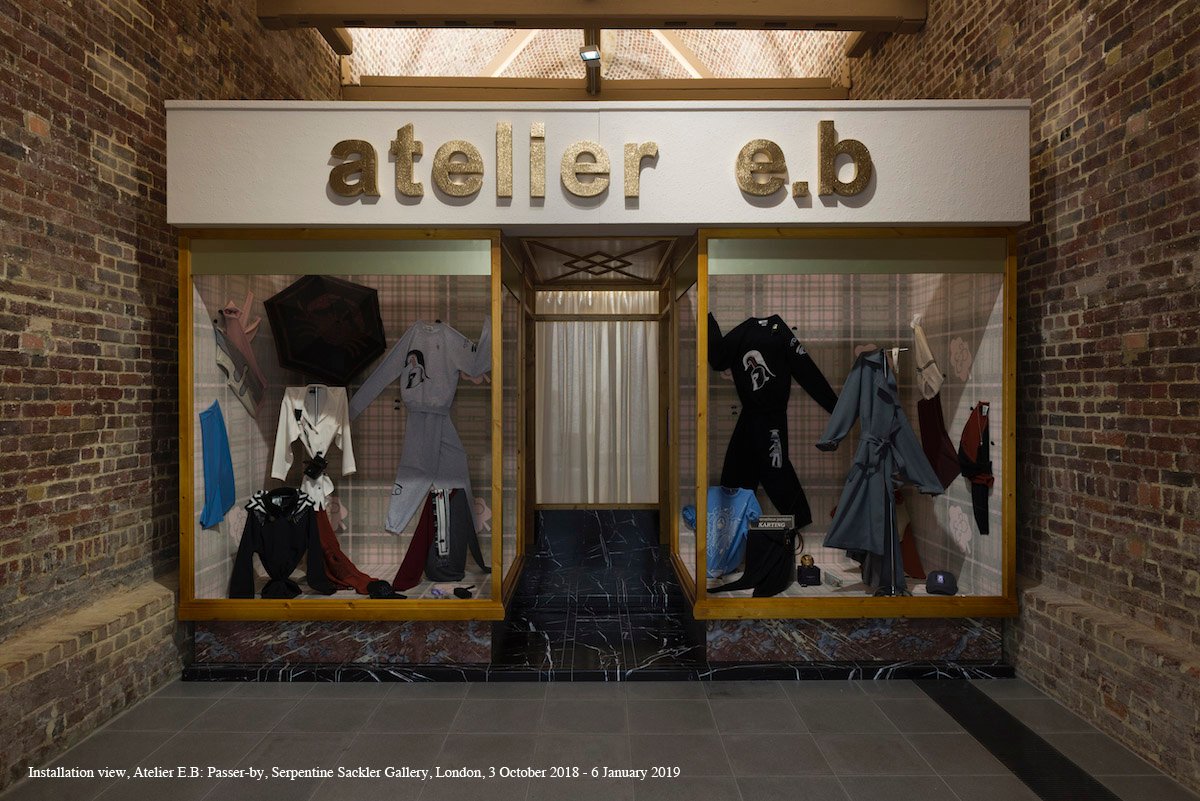

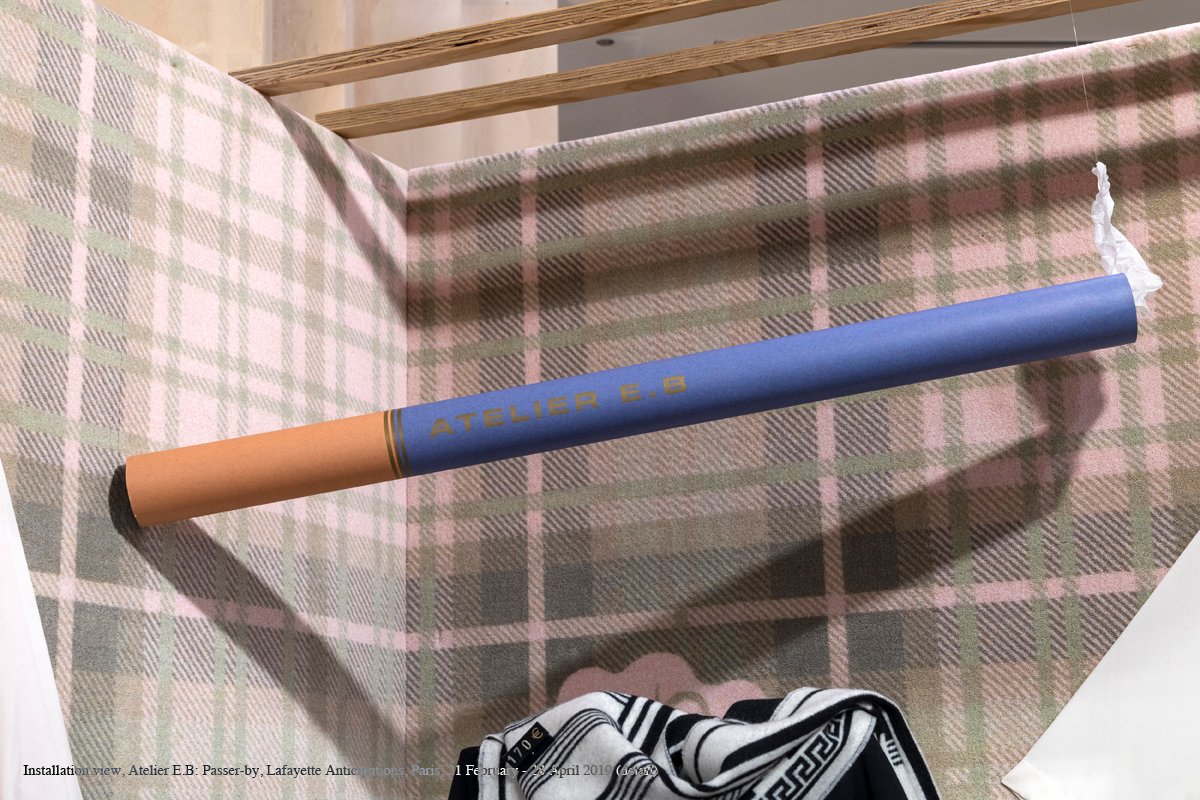

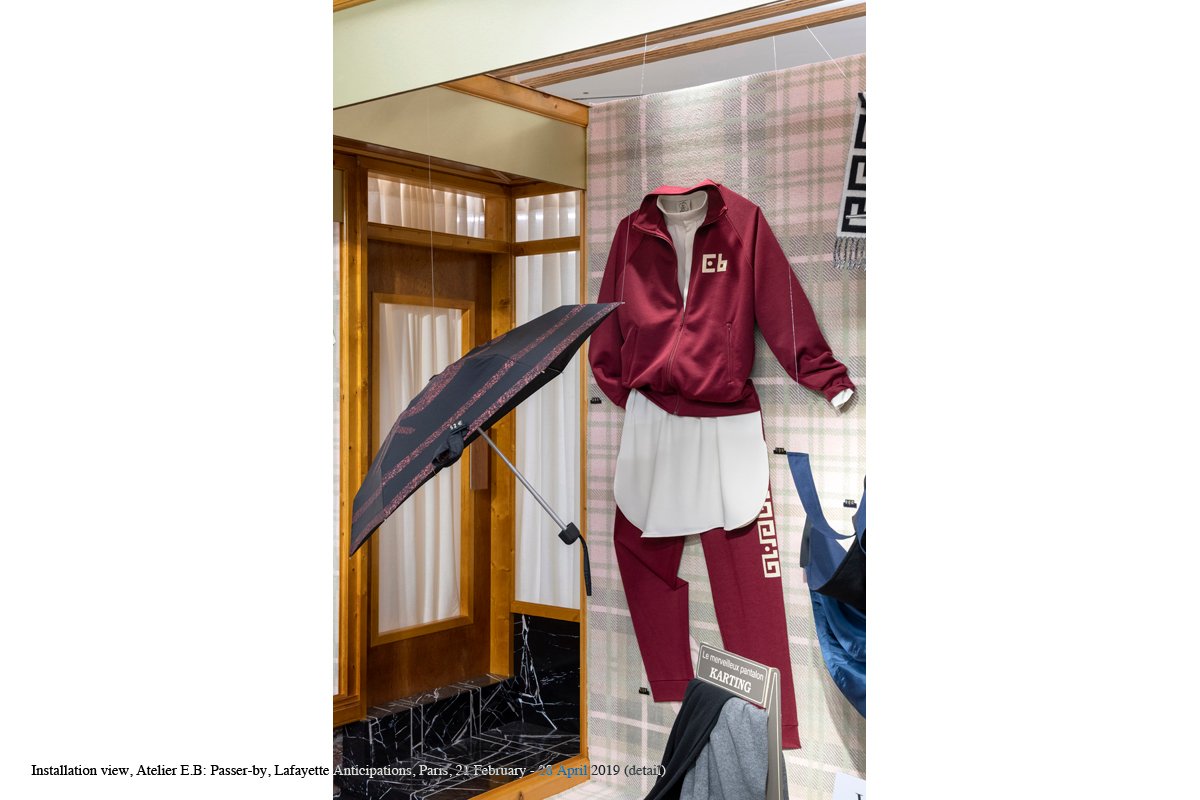

Atelier E.b. (Lucy McKenzie & Beca Lipscombe)

Faux Shop

2018

Mixed Media

450 x 310 x 220 cm

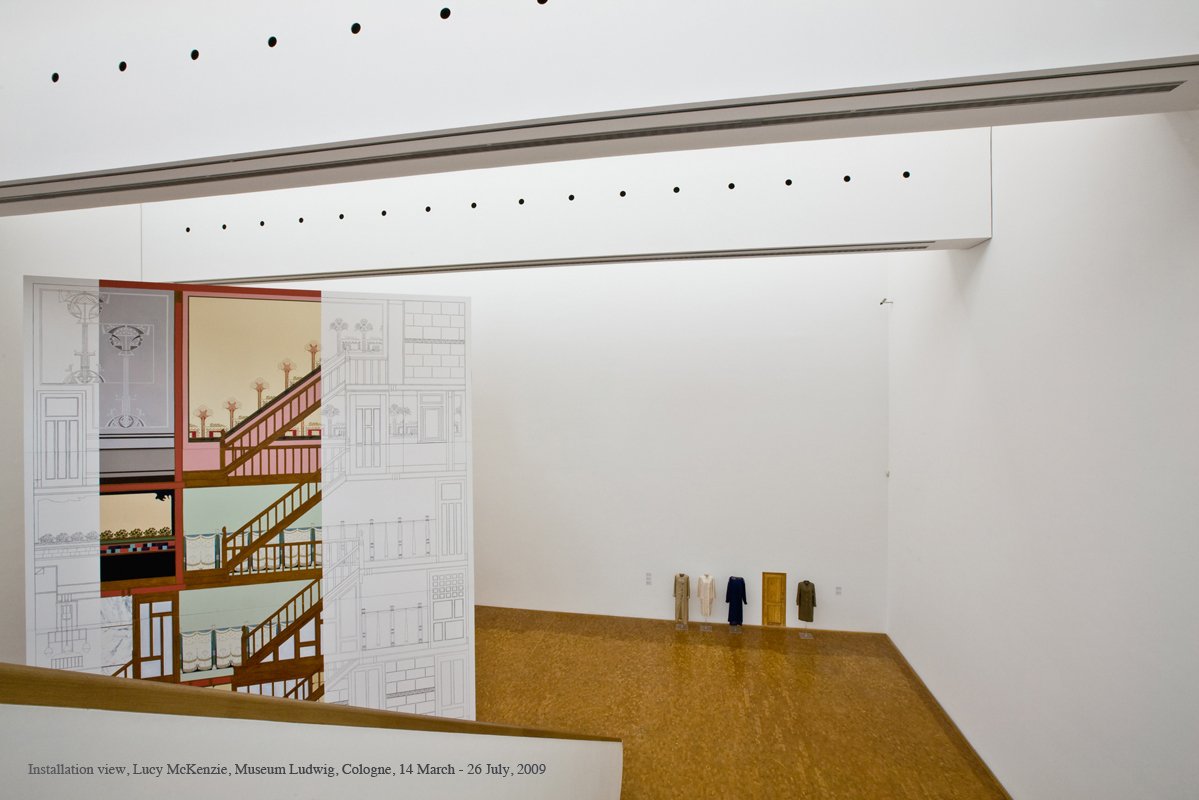

Lucy McKenzie

Ludwighaus

2009

Oil on canvas

Approx. 7 x 8 m / 23 x 26.25 ft

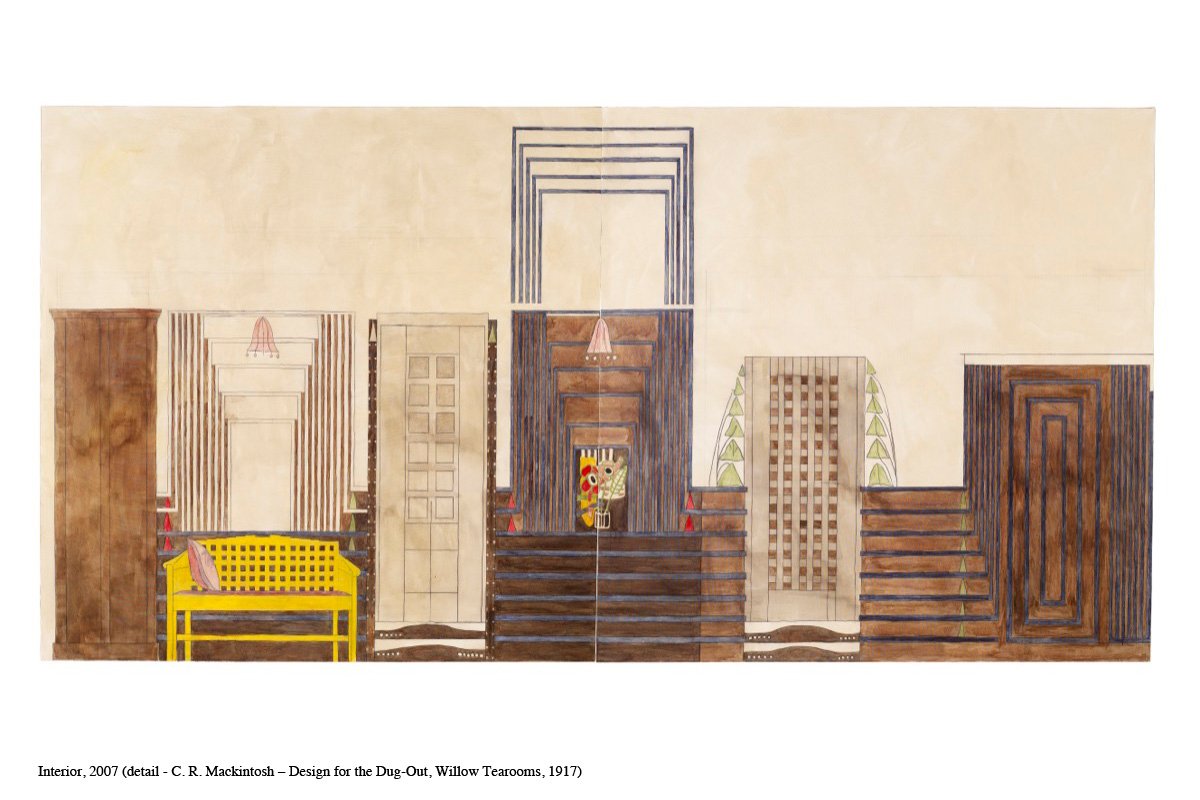

Lucy McKenzie

Interior (P. Jaspar – Michel House, Liège, 1899;

M. Olbrich – Blaues Zimmer auf der Ausstellung Turin, 1902;

C. R. Mackintosh – Design for the Dug-Out, Willow Tearooms, 1917;

P. Hankar – Wijnand Fockink, Rue Royale, Brussels, 1897), 2007

Acrylic and ink on canvas,

4 parts; 300 × 300 cm, 300 × 375 cm, 300 × 600 cm, 300 × 700 cm

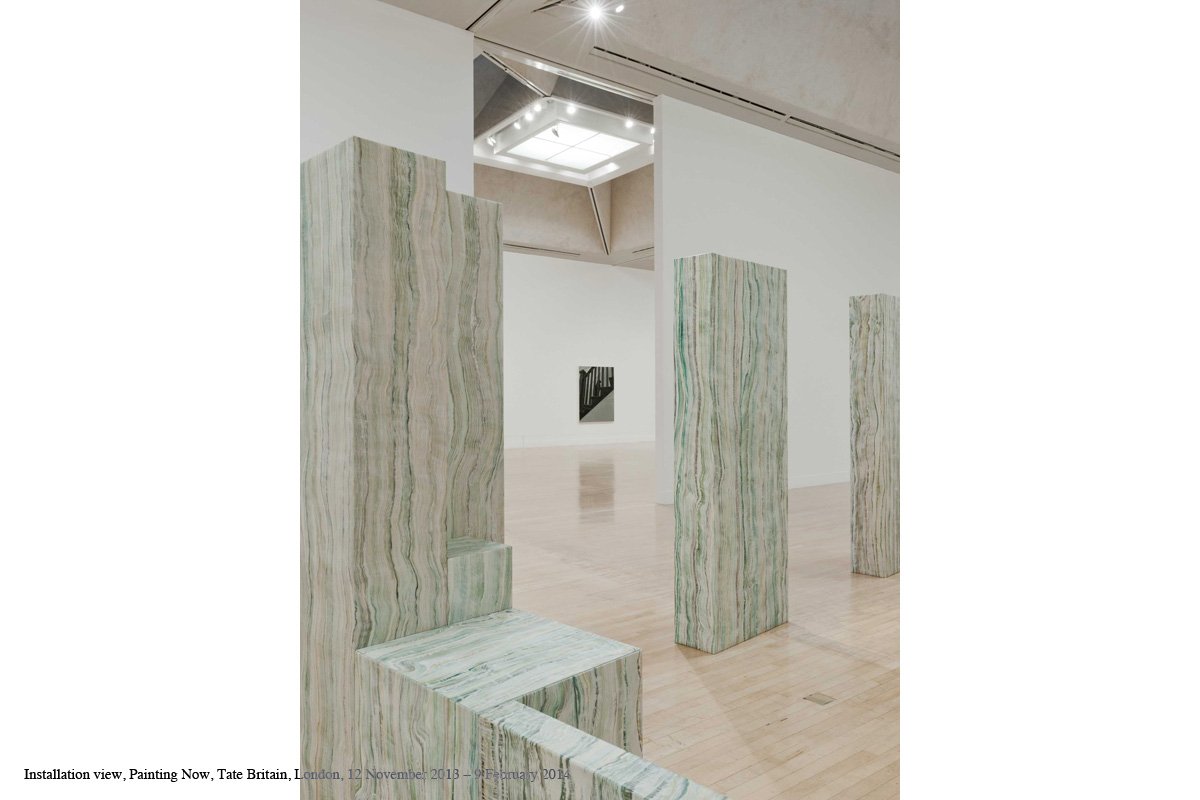

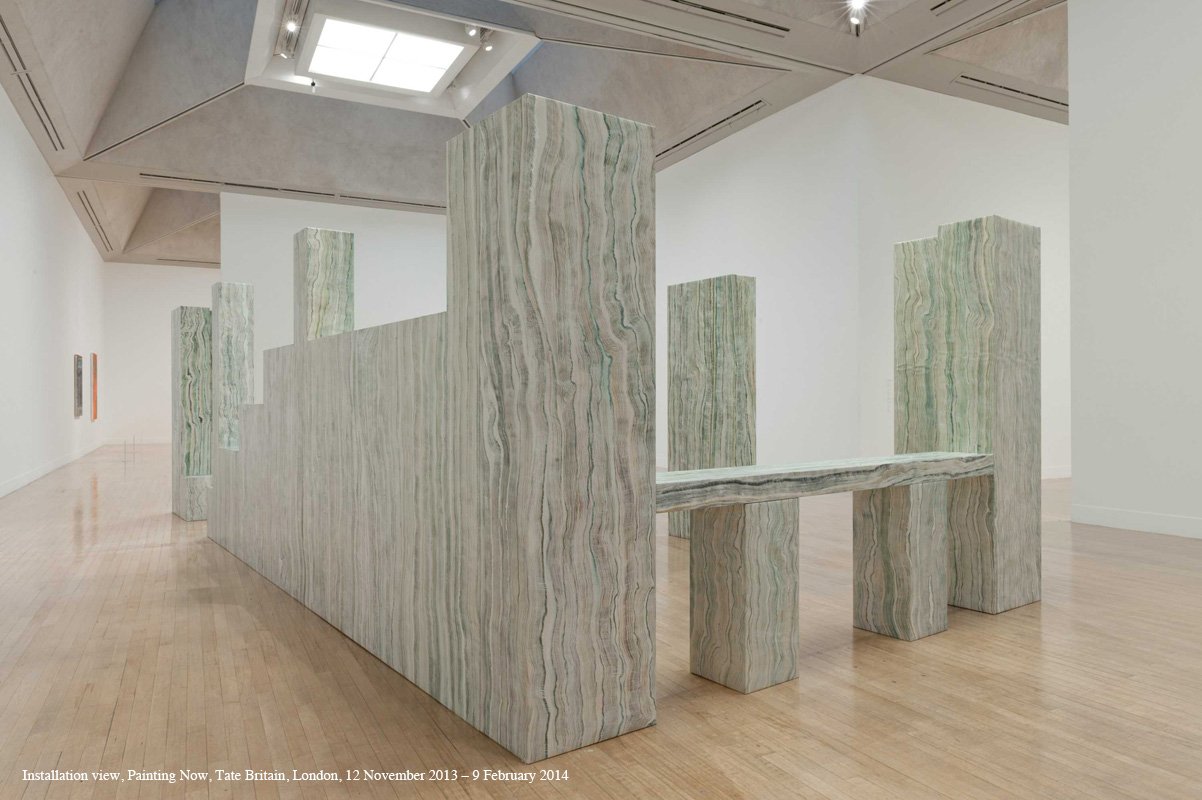

Lucy McKenzie

Loos House

2013

Oil on canvas on wood structure

Installation dimensions variable

Lucy McKenzie

Various early works

1998-2000

Lucy McKenzie

Left - Top of the Will, 1998–99

Photographs, inkjet prints on paper, book and magazine pages, dimensions variable

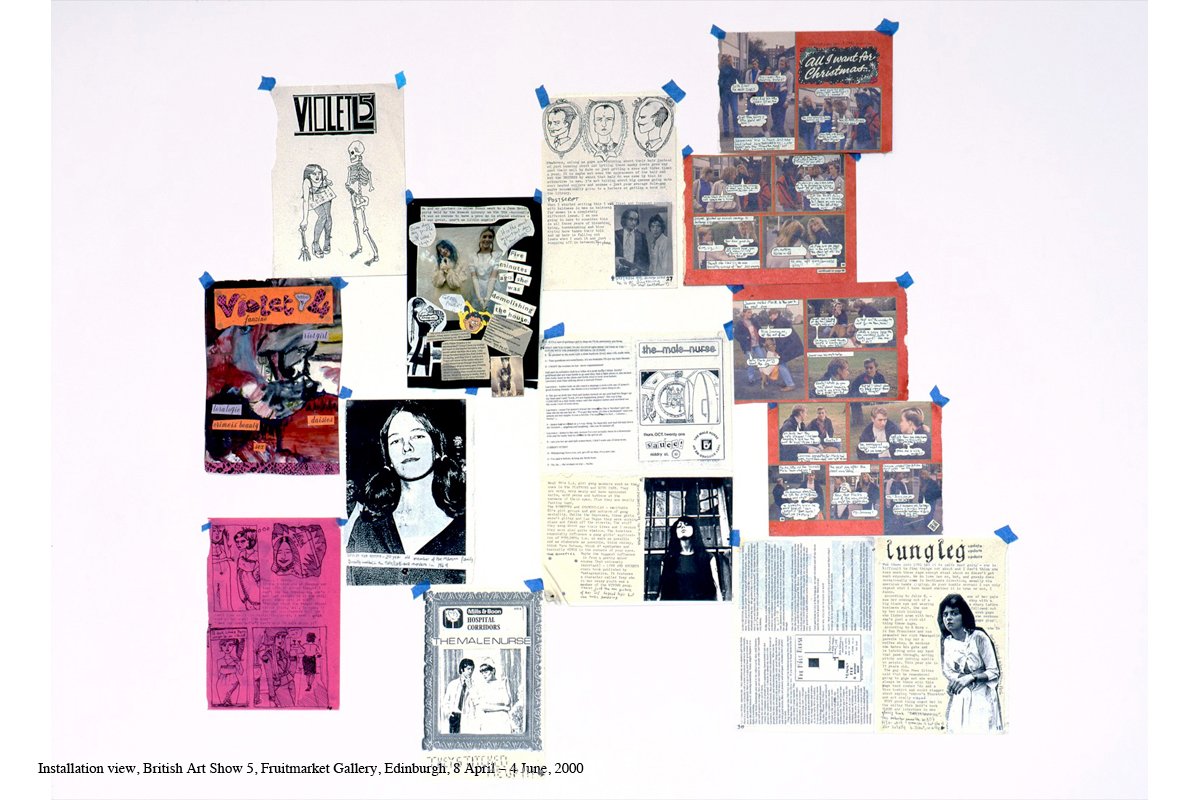

Right - Fanzine (1991–95), 1999

Ink, adhesive putty, and correction fluid on printed paper, photocopies, photographs, adhesive tape, dimensions variable

Lucy McKenzie

If It Moves Kiss It I, 2002

Acrylic on canvas

200 x 323 cm

Lucy McKenzie

Left - Quodlibet XLI (sometimes referred to as Quodlibet XXXXI), 2014

Oil on canvas,

100 × 200 cm

Centre on wall - Quodlibet XXXIII, 2014

Oil on canvas,

180 × 130 cm

Centre foreground - Quodlibet XL (sometimes referred to as Quodlibet XXXX), 2014

Oil on canvas,

60 × 120 cm

Lucy McKenzie

Various Quodlibets including tables and studies on paper

Lucy McKenzie

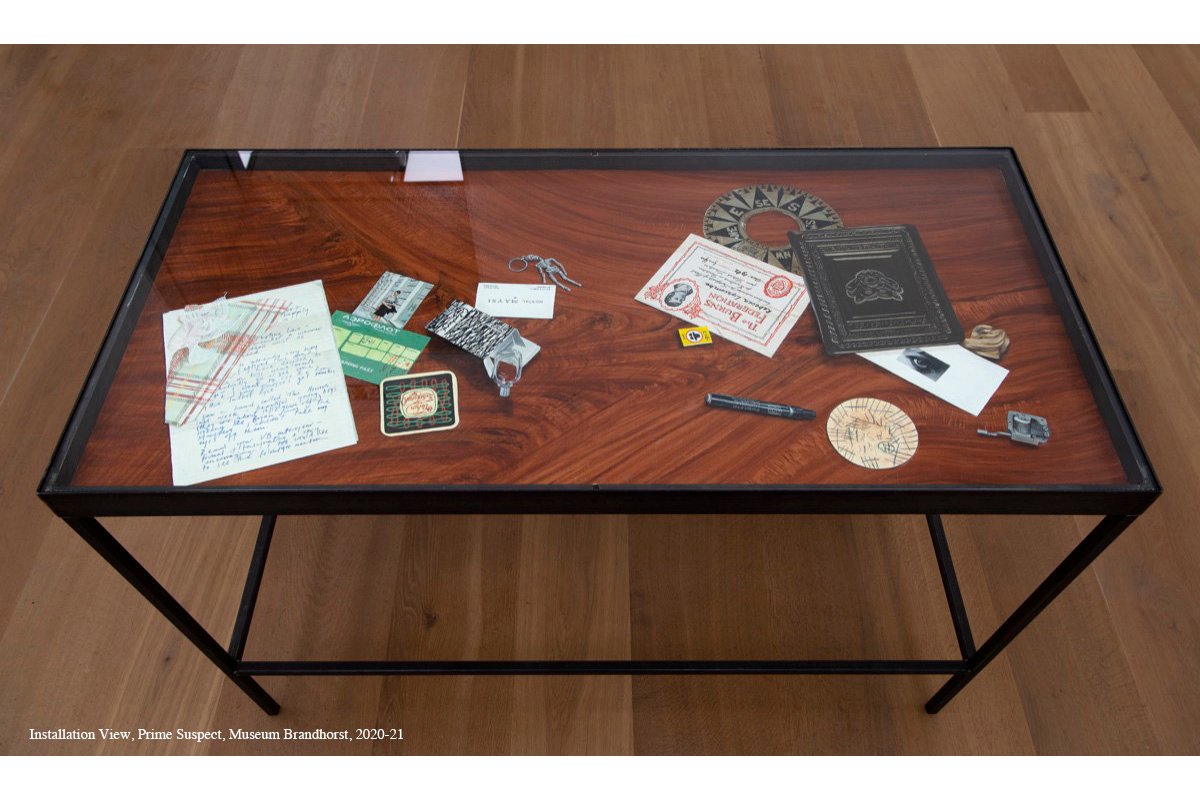

Various works from Giving Up The Shadows on My Face at Cabinet, London, 2019

Installation View, Prime Suspect, Museum Brandhorst, 2020-21

Ars Technica

Jacob Proctor

"If you asked me to just do a painting, spontaneously, from my imagination, I would have no idea what to do. Everything for me is in response to something else."[1]

For more than twenty years, Lucy McKenzie has excavated and transformed images, objects, and motifs from an almost impossibly broad range of historical moments and contexts in the histories of art, architecture, and design; literature, music, and film; fashion, politics, and sport. Beginning in 2008, she has practiced the tradition of trompe I'oeil painting, using it as a means to inhabit, critique, and reimagine earlier eras of art and design; illuminating an alternative history of modern art in which the so-called applied arts emerge as essential actors in a narrative that diverges from the established chronologies of modernism and the avant-garde. Despite her impressive skills as a painter—present from the start but honed by the unusual decision, after several years of success on the international stage, to complete a rigorous course of study in nineteenth-century decorative painting techniques—McKenzie has consistently refused to privilege one form of visual or material production over another. Intentionally or not, this has led her on an idiosyncratic path emphasizing vernacular and collaborative practices long marginalized or denigrated in the context of the fine arts. Her embrace of what she calls "procedural" painting is part and parcel with an approach that treats the medium less as an autonomous art than as a technology, one that is deeply imbricated in the same commercial, industrial, and cultural systems as photography or music.

In McKenzie's earliest body of work, from the late 1990s, we can already see her approaching painting primarily as a reproductive medium. Her paintings of athletes and scenes from Olympic Games are based on mass media representations of these people and events, or staged photographs of herself and her friends in the guise of history. And while there is little that is didactic or overtly political in the works, it is not accidental that McKenzie focused on those games with particularly fraught ideological and political contexts. Her monumental canvas of the Soviet gymnast Olga Korbut, for example, is based on a well-known image of the athlete, her tiny form sliced into vertical strips and reassembled in a manner that literally pulls the image apart

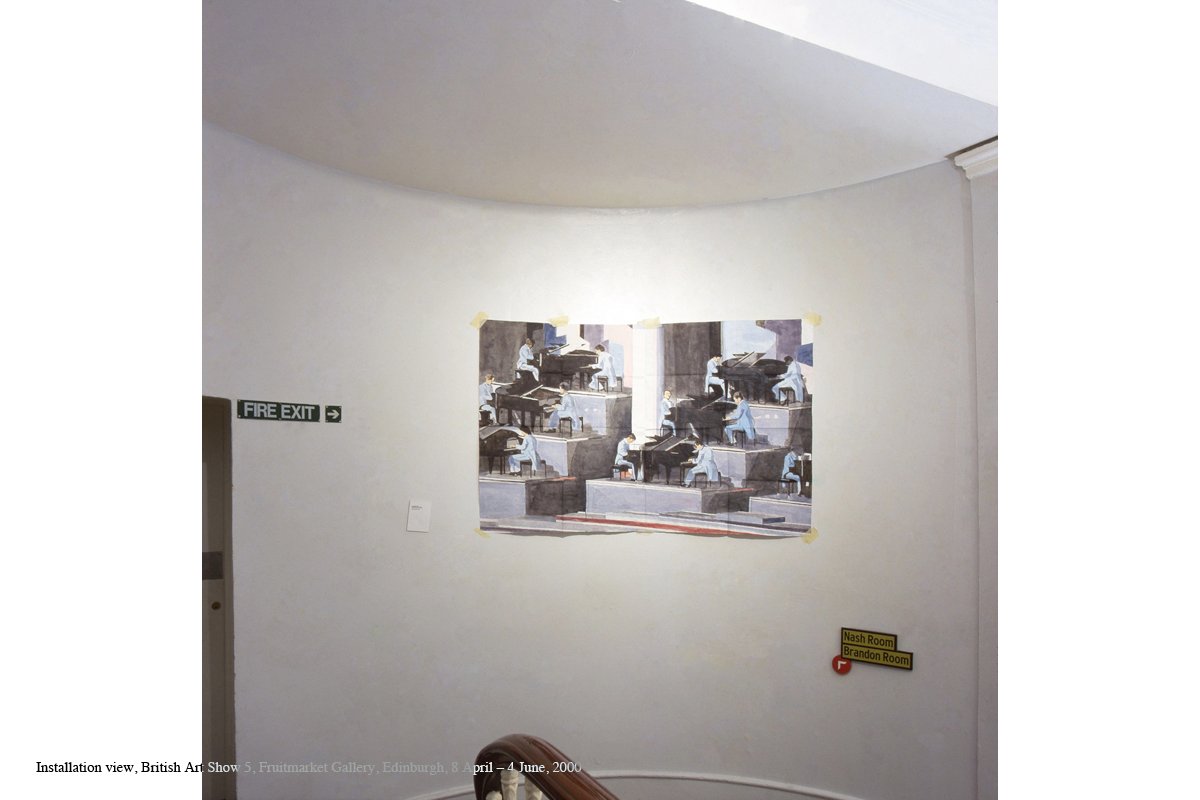

A similar logic of presence and absence exists in McKenzie's paintings based on the 1980 Moscow Olympics (of which the United States led a boycott in response to the Soviet Union's 1979 invasion of Afghanistan) and the 1984 Los Angeles games (boycotted by the USSR and several of its allies in retaliation). In "Three Years to Go" (2000, p. 32), McKenzie subjects a medal ceremony at the Moscow games to the same operation of visual-temporal distension that she had perfected with "Olga Korbut," the painting's crimson palette perhaps reflecting the USSR's domination of the event, not to mention the West's perception of Moscow dominating its neighbors. On the other hand, in "Sport March" (2000, p. 29), the Russian words "cnopTMBHbm Mapuj," repeat up and down the right-hand side of a monochrome grey canvas, their variation in size again suggesting movement or temporal progression, as if the words themselves are marching out of the background. The five colors of the Olympic rings fill one of the central letterforms and extend in thin bands along the painting's outside edges. Here we are reminded how the once-revolutionary vocabulary of Constructivism, shorn of its political context, had—even before the collapse of Communism—been thoroughly absorbed and metabolized by the field of design. In a contemporaneous painting of the Los Angeles Olympic Games, McKenzie overlays the ambiguous title "They Are Lying on Their C.V.s" (rendered in Charles Rennie Mackintosh-style letterforms, p. 28) atop an image of those games' Hollywood-style opening ceremony, a spectacle that included, in a particularly over-the-top bit of symbolism, eighty-four pianists hammering out George Gershwin's "Rhapsody in Blue" in unison.

In "Top of the Will" (1998-99, p. 18), McKenzie supplemented these historical source materials with staged photos of herself and her friends, dressed in gymnastics uniforms based on those worn by the Soviet teams of the 1970s, taped directly to the wall and interspersed with pages torn from vintage books and magazines. In its blend of fact and fiction, documentation and imitation—and a mode of presentation that simultaneously evokes a teenager's bedroom decor and the "evidence wall" familiar to viewers of police procedurals—"Top of the Will" introduces the combination of fan-like enthusiasm and forensic analysis that is among the most enduring features of McKenzie's oeuvre.

As an exchange student in Karlsruhe, in 1998, McKenzie encountered a very different discourse around painting than what she was used to in Scotland. In addition to the already formidable legacy of Martin Kippenberger, who had died the previous year, also present and visible at the time were the collaborative and genre-collapsing multimedia experiments of Cosima von Bonin and Kai Althoff, as well as the latter's strategic embrace of historical codes of cultural (and subcultural) style and taste.[3] In terms of McKenzie's own methodology, if not necessarily her aesthetic, one can discern the impact of an attitude perhaps exemplified by the words of Michael Krebber, who stated in 1994:

"I do not believe that I can invent something new in art or painting because whatever I would want to invent already exists. As a solution,I have chosen therefore not to cease researching. I do not see a great difference between the terms 'composing' and 'interpreting.'"[4]

She was also struck by the peculiar, quasi-religious reception of British post-punk and goth music by many of her German peers.

Both of these experiences would be equally fruitful in her own examinations of cultural difference, coming together in a series of canvases emblazoned with advertisements for club nights and dance parties in Berlin, typography painted directly atop a number of abstract paintings, most of which had been discarded by McKenzie's flatmate at the time, Lucy Henderson, or retrieved from the rubbish bins of her art school in Dundee. In much the same way that the politics and pageantry of international athletics provided McKenzie with a readymade system of conflict and ideology on a grand scale, so the visual language of Berlin's underground dance parties provided another system, this time decidedly more subcultural, to explore. And just as McKenzie inserted herself and her friends into the array of materials in "Top of the Will," so there is an aspect of self-fashioning in her musical references as well. For the youth of McKenzie's generation, sport and music were sites of intense struggle in the articulation one's own individuality within the culture at large; like the tribal allegiance of sports fans to "their" clubs and teams, the music one listened to in many ways defined a person, not only one's taste but one's very identity. At the same time, the coolness of McKenzie's hand-painted yet almost mechanically precise typographic renderings atop fields of anonymous gestural abstraction accentuates the sense that, by the turn of the millennium, the revolutionary potential of abstraction, punk, and new wave alike had already disappeared into the rearview mirror of history.[5]

In both the East and the West, murals, wall paintings, and other forms of public art have long been ambivalent sites for the affirmation and contestation of collective identity. In 2001, following a stint in Berlin, McKenzie created a series of works based loosely on the work of the East German Socialist Realist Walter Womacka. The largest of these, "Global Joy I" (2001, p. 42) reimagines Womacka's "Unser Leben"

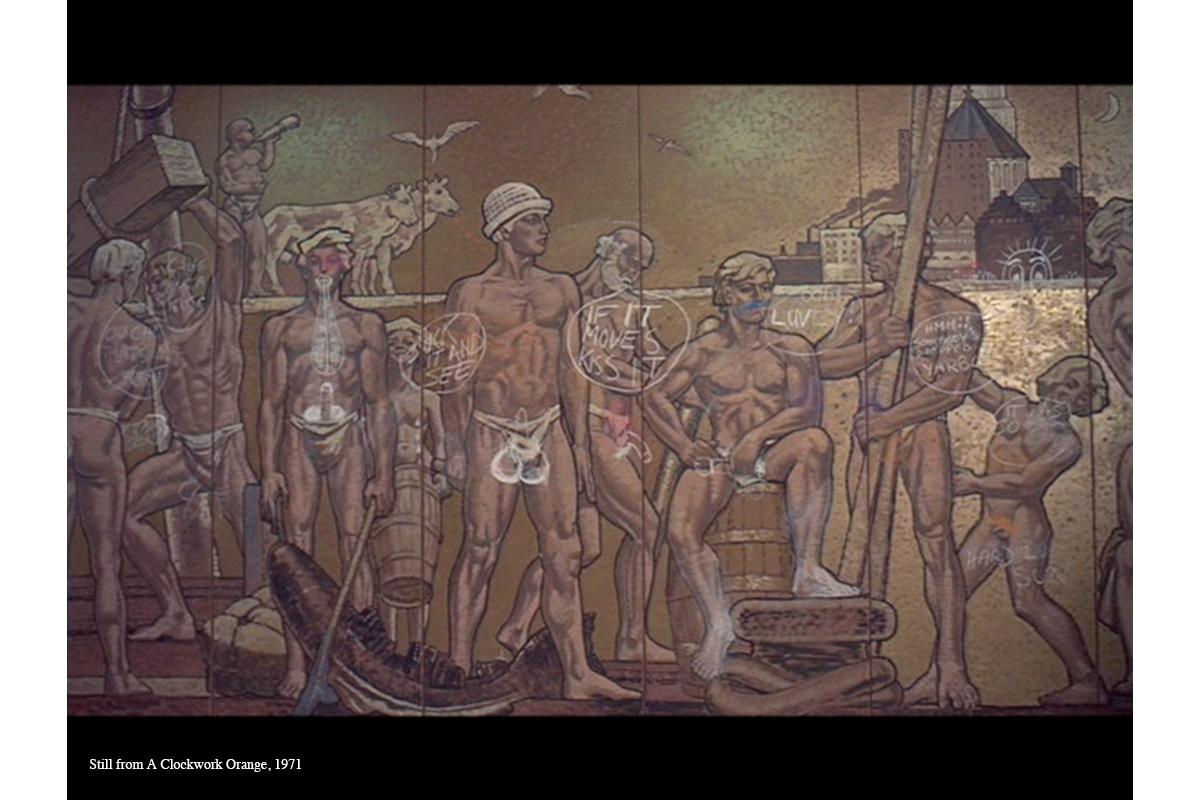

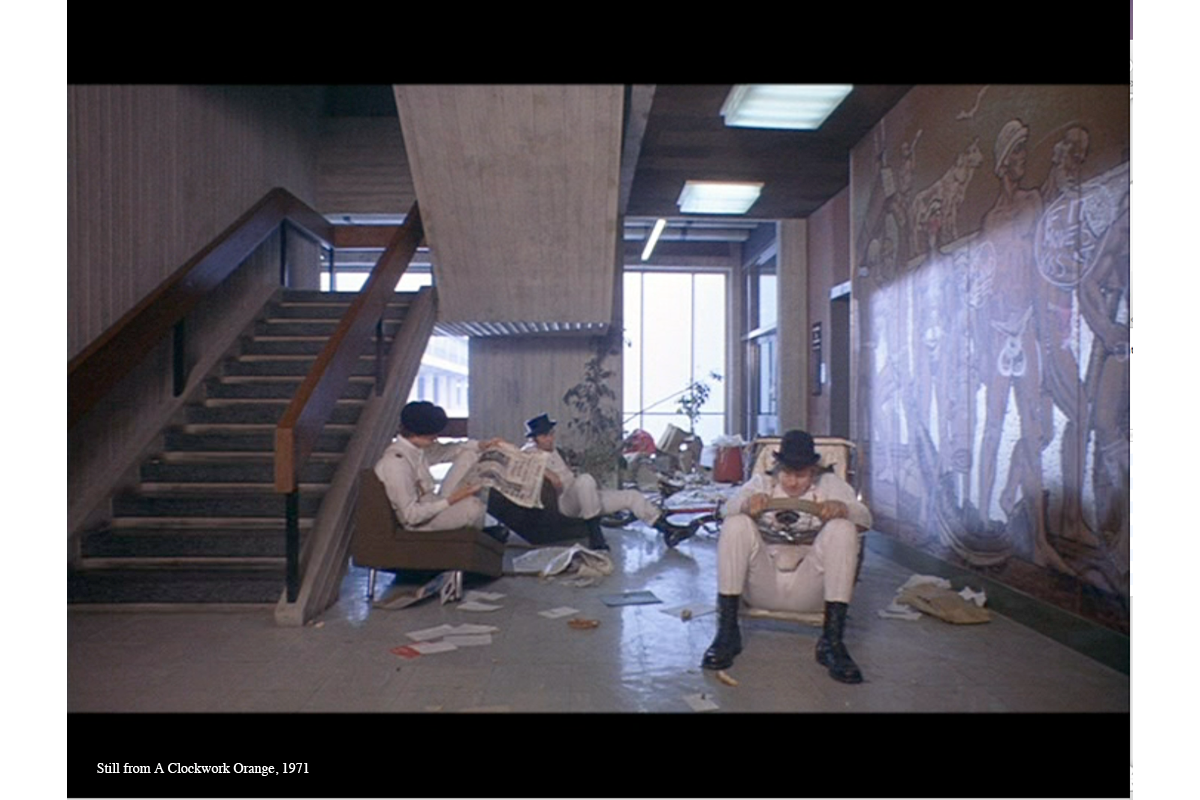

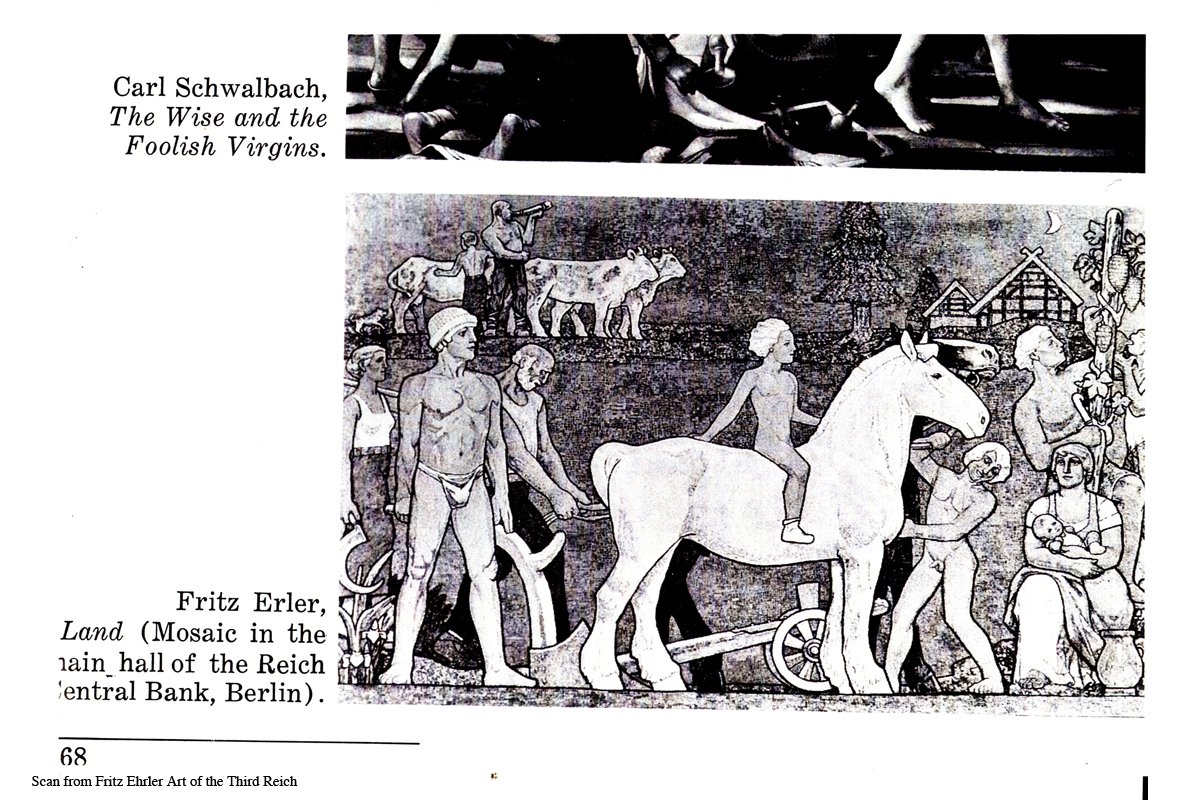

The following year, McKenzie created a suite of works bearing the title "If It Moves, Kiss It." "If It Moves, Kiss It I" (2002, p. 70) is based on a wall painting created as set decoration for Stanley Kubrick's 1971 film "A Clockwork Orange," where it adorns the entry lobby of the apartment block occupied by the film's main character, Alex. McKenzie has noted that she found it especially appealing that this image had been devised by art directors and set directors for the sole purpose of being filmed. Moreover, unlike the other artworks that are featured or referenced in the film, she could find no information about it, suggesting that "it did not seem to be considered of any great significance or artistic importance." She was also interested in the contrast between the musclebound men, clearly intended to convey an aesthetic of totalitarianism, and the mildness of the graffiti itself—phrases like OOHHI! LUVLYI; HMMI! SOMEBODYS PINCHED ME YARBLES; and the titular IF IT MOVES, KISS IT—which she interpreted as "Kubrick trying to tell us that in this future world even forms of rebellion or disaffection, which graffiti represents, are repositioned and divested of their power."[7] By creating two otherwise virtually identical versions of the painting, one with the graffiti and one without, McKenzie isolated the visual- textual image of resistance, positioning it as merely one layer in a more complex system of politics and representation.[8]

In Scotland, muralism played a supporting role in urban renewal projects of the 1960s and '70s. As Victorian tenements were razed and replaced by new motorways and modern, concrete housing developments, murals often served to patch up the wounds inflicted on the city fabric. Although many of its most prominent practitioners viewed their medium as inherently democratizing and themselves as acting in solidarity with the communities in which they worked, their reception often differed significantly within those communities, where they were often met with skepticism and even hostility. "If It Moves,

In 2004, McKenzie was one of several artists invited by Dusseldorf's Kunstverein fur die Rheinlande und Westfalen to produce a proposal for a piece of public art. McKenzie proposed a mural, to be installed on a wall of a newly developed area on the city's harbor, opposite a chic bar. Executed in the distinctive ligne claire style pioneered by the Belgian illustrator Herge (best known as the creator of "The Adventures of Tintin"), the proposed work took the form of a vintage advertisement for a fictional deodorant with a nonsensical name, in which a scantily clad woman has her armpit hair eaten like spaghetti by an entranced group of male admirers as they all get down on the dance floor. While the Kunstverein's competition was underway, McKenzie exhibited a large mock-up of the project, titled "Co? Ne!" (2004, p. 109), in an exhibition at Galerie Buchholz in Cologne, along with a vitrine filled with preparatory studies and source materials including vintage advertisements for brands like Estee Lauder and Elizabeth Arden, photographs of wall paintings in urban settings, a Tintin bookmark, and a page from a pornographic comic book (p. 108). As she noted in her proposal, "historically, public art has rarely been received in the way it was intended, or held in high esteem by the general public ... I give equal consideration to the visual importance of advertising, community murals, graffiti and vandalism alongside civic commissions of sculptures and murals in the urban landscape."[9] Collectively, "Co? Ne!" and its source materials point not only to the ways that murals (including both commercial advertisements and commissioned artworks) have historically served the interests of capital and state power, but also once again to the culture industry's relentless adoption of the tropes of protest and liberation (in this instance of the movement for women's liberation) as a means to market and sell commodities. At the same time, McKenzie's decision to use a commercial gallery exhibition as a means to mediate between the private activity of the studio and the civic service of the public institution served to highlight the fact that artistic activity is also a form of economic activity, and that the system of public commissions and institutions does not operate independent of the market.

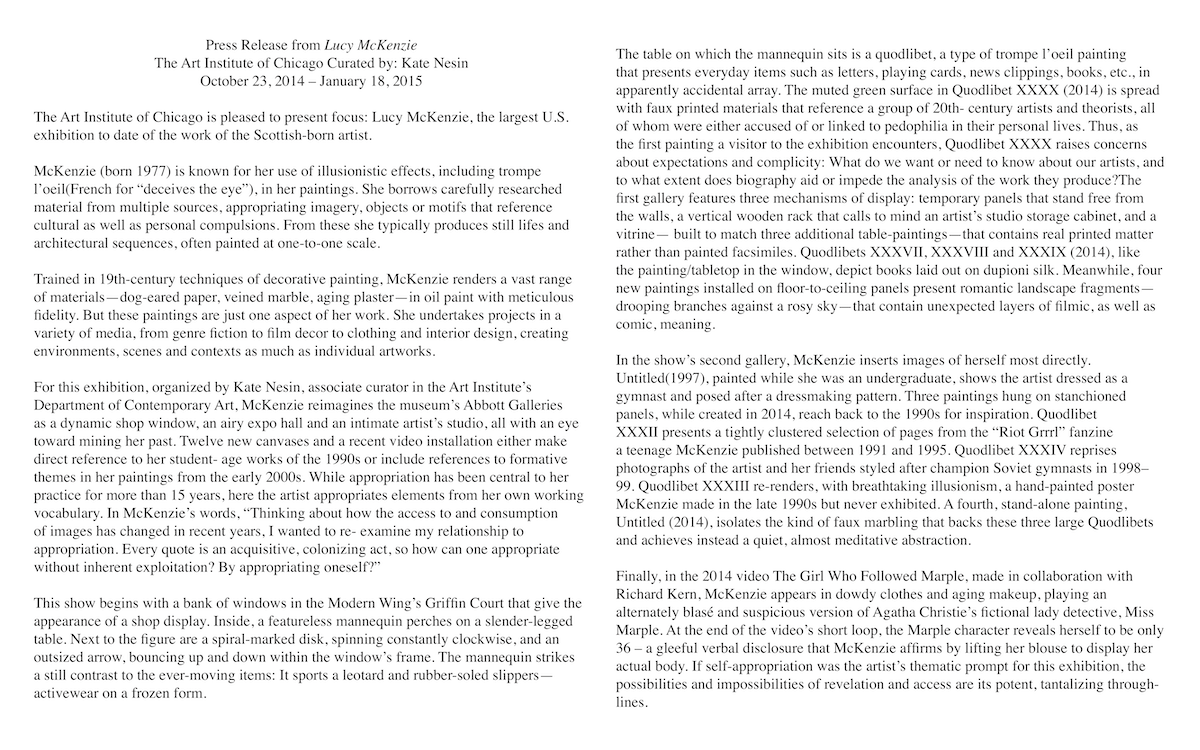

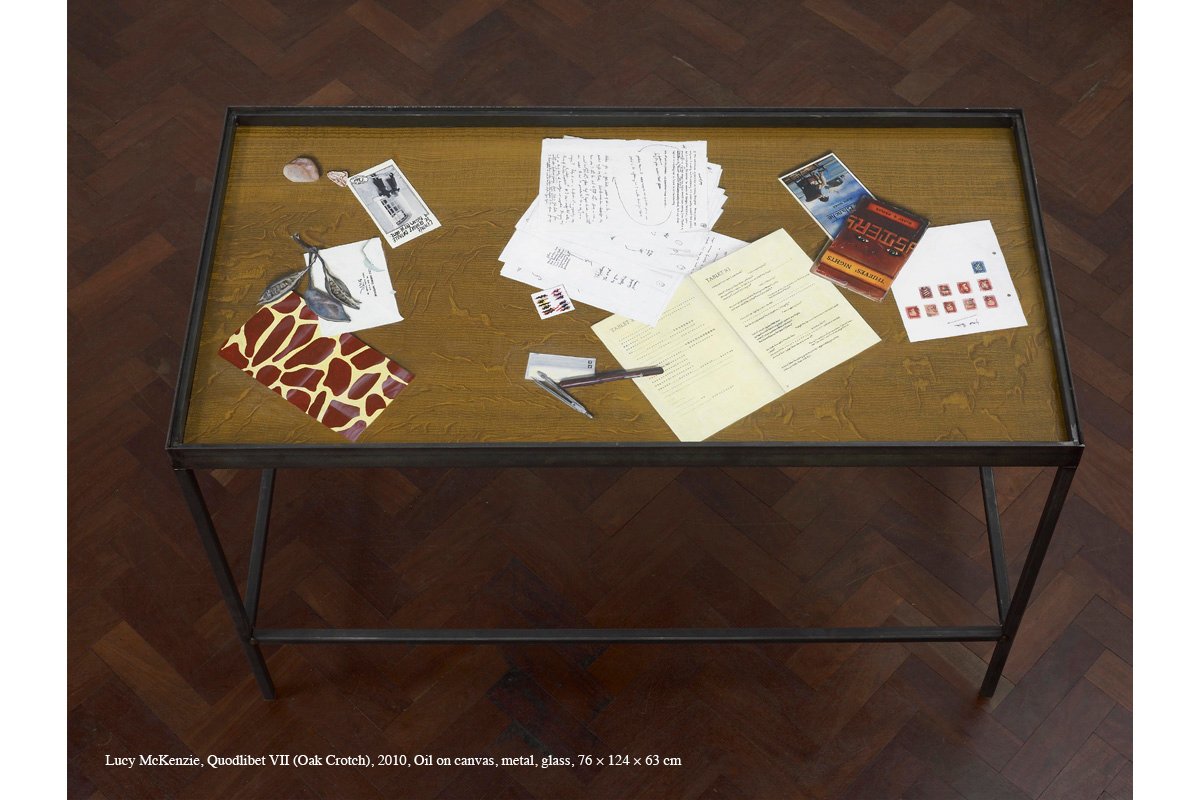

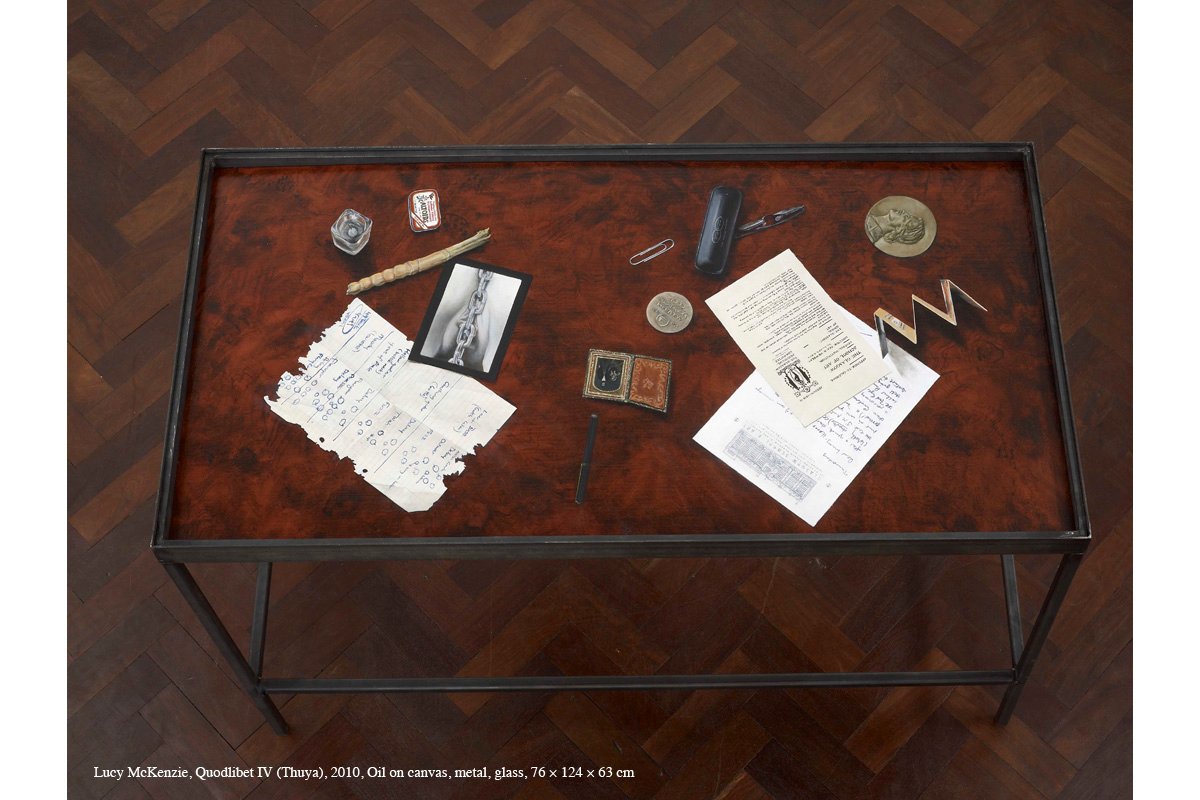

Since 2008, perhaps no format has proven more productive for McKenzie than the quodlibet, a form of trompe I'oeil still-life painting containing various items such as books, letters, scissors, pens, keys, playing cards, and so on, composed as if they were left lying around an arbitrary manner. Despite their initial appearance, quodlibets are quite carefully composed, and the interplay between objects produces subtle narratives for those who look a little closer. As a genre of autonomous paintings (i.e. standalone works not conceived as part of a larger decorative program), the quodlibet emerged in the 1600s, and remained popular through the end of the nineteenth century, with periodic waves of particular enthusiasm at various times and places.

McKenzie first encountered the quodlibet format in 2007-08, when she was required to successfully complete one as part of her coursework at the Institut Superieur de Peinture de Bruxelles Van der Kelen- Logelain (Van der Kelen-Logelain School of Decorative Painting). In that context, in which the labor-intensive nature of illusionistic painting and the traditional alignment of value with craftsmanship reigned supreme, the quodlibet figured as an inherently conservative genre. In McKenzie's hands, however, it has often functioned as a means to question and subvert dominant ideologies and contemporary systems of value.

Since 2008, McKenzie has produced more than sixty-five quodlibets, and has continued to explore the possibilities and limits of the genre. They can, for example, act as an indirect form of portraiture or selfportraiture. "Quodlibet XIII (Janette Murray)" (2010, p. 152) and "Quodlibet XII (Steven Purvis)" (2011, p. 153) depict their subjects through the quotidian equipment of their respective professions in the Scottish textile and garment industries. In the former: a map of Scotland, knitting patterns, thread samples, knitting needles and a ball of wool, and so on. In the latter: scissors, buttons, fabric samples, business cards, and correspondence, among other items. "Quodlibet XL" (2014, p. 206) can be understood as a kind of group portrait, depicting, from left to right, works by the artists and theorists Eric Gill, Otto Muehl,

Two types of quodlibet paintings—pin-boards and tabletop arrangements—have been central to McKenzie's work, although she has also extended the notion of the genre to encompass entire pieces of trompe I'oeil furniture, such as desks, dressing tables, file cabinets, and wardrobes. These more recent works hark back to a related tradition of trompe I'oeil paintings known as chantournes (from the French verb chantourner, meaning to cut according to a determined profile), in which the shape of the painting is fully congruent with the object represented. At approximately the same moment, McKenzie decided to collage actual paper documents into some of her painted quodlibets ("Quodlibets L and Llll," 2015, pp. 222-25). Here, the intention was to destabilize, even undermine, the equation of value with virtuosity that she herself established in her earlier works. This move complicates the already unstable perceptual relationship between the thing and its representation that undergirds the entire trompe I'oeil enterprise. Whereas McKenzie's trompe I'oeil furniture pushes to the limit the identity of the painting with the object represented, the importation of the object itself, in the form of a printed document, both absorbs and rejects the entire premise of painterly mimesis. In this, McKenzie both revisits a central visual problem of cubism and updates it for the digital age. After a number of years, viewers of McKenzie's work—having grown familiar with the conventions of trompe I'oeil in her work—would naturally expect to encounter an expertly painted representation of a document, a book jacket, or any other object. Confronted instead with the object itself, nestled seamlessly within an otherwise i 11 usion istic (painted) context, the contemporary viewer confronts anew the question of the ontological status of the image. At the same time, the particular nature of the collaged elements—various pieces of business correspondence related to Atelier E.B—reflects McKenzie's own embeddedness in a society and culture of administration.

Given her longstanding interest in forms of visual representation that have historically existed outside the fine arts, especially those that appear in or in relation to the public sphere, as well as in constructions of national or collective identity, it was perhaps inevitable that McKenzie would turn her attention to cartography. The image of a map first appeared in a pair of portraits, "Kerry" and "Keith" (both 2001, pp. 44 and 45), each of which visually rhymes the schematic outline of a wall- mounted map with the large cast shadows of their titular subjects. In 2014, McKenzie painted four large canvases collectively entitled "Phallic Map Mural for Brasserie Scene in Unrealized Kubrick Film" (pp. 216-21). The idea for the series came to McKenzie in a dream, where the paintings functioned as decor in a restaurant scene in the film. In the paintings, the drooping forms of tree branches studded with flowering buds suggest the vaguely phallic outlines of, respectively, the island of Manhattan, Lake Geneva, the conjoined peninsulas of Sweden and Finland, and Scotland's Mull of Kintyre. (According to legend, the British Board of Film Classification had purportedly used the latter as a barometer by which to judge the appropriateness of images of naked men on screen: the angle of a man's penis could not appear to be more erect than cartographic outline of the Scottish peninsula.)[10]

Maps, like all other technical forms of rendering, are nevertheless rhetorical devices. Like any other discursive system, they are governed by rules and codes of meaning production. Although they may go to great lengths to appear neutral, they are, in fact, anything but. Neither passive reflections of the world nor mere bureaucratic instruments, maps are, in Foucauldian terms, both a form of knowledge and a form of power.[11] McKenzie's appropriations highlight the ways that maps— both decorative and functional—are ways of conceiving and structuring the world, and therefore deeply ideological.

At Buchholz, McKenzie's paintings joined trompe-l'oeil painted desks, chairs, filing cabinets, beds, tables, a wardrobe, as well as numerous paintings, in an elaborate mise-en-scene simulating the interior furnishings of a private apartment or office (pp. 214-15, 223, 226-27). When they were subsequently exhibited at Galerie Buchholz's New York space in 2016, the furnishings were installed on low plinths and accompanied by an elaborately detailed auction house-style catalogue, complete with physical descriptions, condition reports, provenance, and literature for each piece (p. 238). Although this document was, ultimately, a work of fiction, McKenzie inserted enough factual information to lend it a veneer of plausibility.

The following year, McKenzie included four large map paintings in her exhibition "La Kermesse Heroique" at the Fondazione Bevilacqua in Venice, three referring to transportation hubs and networks. In "Congonhas-Sao Paulo Airport," (2017, p. 262) a map of Brazil is adorned with stylized renderings of people, animals, buildings, and vegetation illustrating the characteristic economic and leisure activities, climate, and architecture of the country's many regions, while "Budapest" (2017, p. 265) visualizes a network of land, air, and sea transportation routes emanating outward from the Hungarian capital. "Ghent-Sint-Pieters" (2017, p. 266) is more visually and historically complex. The Ghent St. Pieters train station was completed in 1912, just in time for the Exposition universelle et internationale in 1913. In addition to the well-known murals in the main arrivals hall, a side hall held a large mural depicting the extensive European network of railways, extending from London to Moscow (a system that would be profoundly disrupted with the start of World War I the following year). At some point in the 1960s, the mural was overpainted with a collection of cartoonishly generic signifiers of a pseudo-medieval past (p. 268). Perhaps, with the Iron Curtain firmly dividing Europe, there was a sense that such links would never be reconstituted; or perhaps it was done as a kind of municipal self-fashioning, catering to a new class of tourist looking to visit its well- preserved medieval architecture, which escaped World War II largely intact. During a recent renovation, the original mural was rediscovered, and a thin vertical section of the overpainting removed (a second small area of removal is visible in the upper right corner). It is unclear why the painting was left in this arrested state of restoration, but it was precisely this palimpsestic state of overlapping temporalities and visual languages that appealed to McKenzie.

Through these kinds of borrowings—technical, stylistic, material, historical—McKenzie demonstrates that categories like "painting" and "drawing" not only exceed the boundary of any particular artwork but extend well beyond the fine arts, popping up unexpectedly in different historical and cultural contexts. Borrowing and repurposing a metaphor from the late Italian curator, critic, and art historian Germano Celant, we might imagine this expanded field of painting as "an enormous roll of diversified fabric, woven in a single piece and unrolled in time and in space. This surface extends for miles and miles but never appears on display."[13] A painted sign hung outside a shop, a mural in a train station, an advertisement on the side of a building; all share the same essential genetic material as a canvas hanging in a private home or a public museum. And while the meaning of each is subject to the specificity of its own historical and cultural context, we can image that they are each cut from different areas of the same enormous canvas. In this light, McKenzie's project can be understood as a practice of erasing the distinctions—material, procedural, perceptual—between the subjects, objects, competencies, and architectural and social spaces that have narrowly defined painting as an artistic practice in the modern era.

Further reading

Click on each link below to download

by Barbara Engelbach

from Chêne de Weekend

Lucy McKenzie 2006-2009

Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König 2009

0.91mb

‘Lucy McKenzie: Manners’

by Ilsa Leaver-Yap

from Afterall, Autumn Winter 2013

6mb

‘A Restless Subject’

by Milovan Farronato

from Flash Art November - December 2013

4.3mb

‘Adventures Close To Home: Lucy McKenzie and Marc Camille Chaimowicz’

by Michael Bracewell

from Mousse Magazine, Issue 29, Summer 2011

1.3mb