Lucy McKenzie

Lucy McKenzie

Approval of the Committees

17 November 2022 - 21 January 2023

C A B I N E T

132 Tyers Street

Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens

London SE11 5HS

Street Vitrine II (Niche) presents a selection of mostly hand intarsia garments spanning from 2011- 2021.A few of these garments were made at Ballantynes before it ceased to function in 2013. In 1921, the sons of David Ballantyne formed D. Ballantyne Brothers and Co. Ltd., a cashmere knitting factory in Innerleithen, Scotland. During the 1950s, the company moved into the fashion sweater market, rebranded as Ballantyne Sportswear Co. Ltd. , developing intarsia designs that appealed to people of sophisticated taste. Ballantyne was recognised as one of the finest makers of cashmere in the world.

Street Vitrine II (Niche) was dressed by Barbara Kelly and Howard Tong. Barbara Kelly dressed the windows for Berk, Burlington Arcade, 1998-2016, who sold Ballantyne and John Smedley - inspiration for the Niche vitrine.

Precisely (and while resolutely plying her own course) McKenzie reconciles two political strands in the making of art: political in the sense of “popular”, sharing forms that speak to individuals at all levels of society, and political in the sense of “progressive” – offering a critical, reformist vision of reality.We see how far her work, its economic roots in everyday reality, its blurring of codes and messages – sets out deliberately to break the separatist pact between contemporary art and the rest of the world. Hers is a practice which, though peppered with references to the “official” history of Western art, flirts endlessly with the margins to shift and decentralise its dominant axis, at a time when our need for multiple narratives has become a matter of survival.

Atelier E.B, Street Vitrine II (Niche), 2020-22

Atelier E.B, Street Vitrine II (Niche), 2020-22Installation View, Lucy McKenzie, Approval of the Committees, Cabinet, London, 17 November 2022 - 21 January 2023

Atelier E.B, Street Vitrine II (Niche), 2020-22

Atelier E.B, Street Vitrine II (Niche), 2020-22Installation View, Lucy McKenzie, Approval of the Committees, Cabinet, London, 17 November 2022 - 21 January 2023

Lucy McKenzie, On The Prowl, 2021-22

Lucy McKenzie, On The Prowl, 2021-22Installation View, Lucy McKenzie, Approval of the Committees, Cabinet, London, 17 November 2022 - 21 January 2023

Courtesy BY ART MATTERS (https://www.byartmatters.com/en.html)

Lucy McKenzie, On The Prowl, 2021-22

Lucy McKenzie, On The Prowl, 2021-22Installation View, Lucy McKenzie, Approval of the Committees, Cabinet, London, 17 November 2022 - 21 January 2023

Courtesy BY ART MATTERS (https://www.byartmatters.com/en.html)

Lucy McKenzie, House of Prototypes, 2021-22

Lucy McKenzie, House of Prototypes, 2021-22Installation View, Lucy McKenzie, Approval of the Committees, Cabinet, London, 17 November 2022 - 21 January 2023

Courtesy BY ART MATTERS (https://www.byartmatters.com/en.html)

Lucy McKenzie, House of Prototypes, 2021-22

Lucy McKenzie, House of Prototypes, 2021-22Installation View, Lucy McKenzie, Approval of the Committees, Cabinet, London, 17 November 2022 - 21 January 2023

Courtesy BY ART MATTERS (https://www.byartmatters.com/en.html)

Lucy McKenzie, House of Prototypes, 2021-22

Lucy McKenzie, House of Prototypes, 2021-22Installation View, Lucy McKenzie, Approval of the Committees, Cabinet, London, 17 November 2022 - 21 January 2023

Courtesy BY ART MATTERS (https://www.byartmatters.com/en.html)

Lucy McKenzie, On The Prowl, 2021-22 (detail), Installation View, Lucy McKenzie, Approval of the Committees, Cabinet, London, 17 November 2022 - 21 January 2023

Lucy McKenzie, On The Prowl, 2021-22 (detail), Installation View, Lucy McKenzie, Approval of the Committees, Cabinet, London, 17 November 2022 - 21 January 2023Courtesy BY ART MATTERS (https://www.byartmatters.com/en.html)

Lucy McKenzie, On The Prowl, 2021-22 (detail), Installation View, Lucy McKenzie, Approval of the Committees, Cabinet, London, 17 November 2022 - 21 January 2023

Lucy McKenzie, On The Prowl, 2021-22 (detail), Installation View, Lucy McKenzie, Approval of the Committees, Cabinet, London, 17 November 2022 - 21 January 2023Courtesy BY ART MATTERS (https://www.byartmatters.com/en.html)

C A B I N E T

Lucy McKenzie grew up in Glasgow and since 2006 has lived in Brussels, Belgium. Her work combines traditional oil painting with a variety of other disciplines including collaborations in fashion and furniture design, curation, writing, and publishing. This, her first solo exhibition in London since 2010, explores the intersection of fine and applied arts, representation and labour in a series of paintings and objects.

Together with Beca Lipscombe, her long-term collaborator in the fashion label Atelier E.B, McKenzie staged Atelier E.B: Passer-by at Serpentine in 2018 and Lafayette Anticipations in Paris in 2019. The exhibition examined the fruitful exchange between retail display / mannequins and fine art. In Giving Up The Shadows On My Face McKenzie continues to explore the artist-mannequin partnership and examine the dynamism that is created when different creative fields are brought into dialogue.

Mural painting and the decoration of civic spaces have long been a forum in which ideology and cultural policy have come to artistic fruition:

The monumental wall painting, a prestigious format in Europe since the Middle Ages, became a fulcrum of critical debate in the 20th century. Many artists and critics looked to the mural as a corrective to the ills of painterly Modernism: the disruption of the pictorial field at the hands of Cubism and other avant-garde practices; the commodification of painting through the market for easel paintings; the loss of arts effective public mission; the erosion of aesthetic aura; and more generally the alienation of man and the anomie of art in the modern condition.

At the same time it was clear that a return to the mural format would never be more than anachronistic and futile gesture.

Romy Golan, Muralnomad: The Paradox of Wall Painting, Europe 1927-1957

For Giving Up The Shadows On My Face McKenzie highlights the friction between two artistic systems, art made for the private market (as typified by the framed oil painting or the display vitrine) and that supported by the state (here represented by a Soviet-era style mural). She examines the way these two methods of artistic expression (and economic survival) are aesthetically shaped by those systems, what defines them, and how this relates to artistic hierarchies.

A vitrine is used as a framing device to give value to and elevate a household chair (a replica from the 1930s villa by the by Belgian architect Josef De Bruyker that the artist is restoring). The vitrine is one of a pair that would sit well somewhere like the Burlington Arcade, but their interiors are fitted with replicas of the kind of marble that decorates the civic buildings of Totalitarian states (here taken from EUR, the neighbourhood of Rome planned under Mussolini in the 1930s). These painted interiors also recognise the contemporary vogue for marble in designer boutiques—which take their cue from marble’s re-emergence in the 2010s as a sculptural material in visual art, rather than directly from luxury décor. In the show the chair is presented as a functional design object, displayed in a vitrine and as part of a painted composition: domestic, commercial, creative and civic spheres are overlaid.

Glasgow 1936 / 1966 depicts two maps of central Glasgow superimposed upon each other, a tram map from 1936 and a gang territory map from 1966. The work was originally painted as a commission for a public museum, responding to the remit of the institution. But the deal went sour, and now it’s for sale in a private gallery.

Even more than the oil painting, fashion is creativity driven by the free market, so bringing together haute couture and public art can create an even more fractious polemic. Theoretically, fashion is the manifestation of the desires of the individual, often considered an indulgent and corrupting pleasure, in opposition to the healthy, edifying role that public art plays in improving society. It is perhaps the incessant failures of these two forms to deliver on their promises that makes them such potent forms.

Labour is not merely the expenditure of energy; within Socialist Realism, it and the labourer are heroic subjects. Labour is also an essential component of haute couture. Together with her assistants McKenzie made a replica of a 1933 couture dress by the celebrated French designer Madeleine Vionnet, and it features in the exhibition in several of the works. A tabletop trompe l’oeil still-life depicts the process of replication: it clothes a handmade mannequin in one of the display vitrines, and is worn by the same mannequin in the painting Rebecca. Painting is used to ‘intervene’ at different stages of processes that illustrate labour as both method and subject.

McKenzie’s interest in painting is rarely for its own sake. Rather it is painting as it often relates to decorative and commercial art. Hers is a prosaic rendering of real spaces and objects in one-to-one scale, done using the procedural, mechanical techniques she mastered as a decorative painter.

The objects and scenes she depictes often relate to by-gone eras. Anachronism is deliberately employed as a distancing device to reflect on contemporary attitudes and thinking. The defining characteristics of an epoch are often imperceptible until it is superseded and consigned to the past. Her layering of period styles speaks truth to how eras do not merely start and stop but overrun and spill. To illustrate this, replication offers a way in. For Atelier E.B: Passer-by McKenzie made a trompe l’oeil copy of the 1939 work Trial and Error by the British painter Meredith Frampton (the style and composition of which also underpins the construction of Still-life, on view here). A replica can never be a ‘perfect copy’, the aesthetics of its period will always subconsciously impose themselves.

This in turn is why the fashion mannequin is of such relevance: its body shape and formulaic poses reflect the aesthetics ideals of its period, the pure capitalist body, coming into and going out of fashion at an accelerated pace. The mannequin that features throughout the show is a hybrid between a fashion display doll and a statue, its head being a 3D scan of an unattributed bust in the collection of the plaster cast workshop of the Royal Museum of Art and History in Brussels. But its painted surface robs it of its high cultural value and renders it uncanny. Polychrome debases it and links it to the popular arts of marionettes, religious statuary and sex dolls.

In the hands of the Surrealists the figure of the mannequin was subverted through fragmentation. This is one of the defining characteristics of high modernism that has greatly influenced notions of beauty. The complex relationship between artist and mannequin predates the Surrealists by at least a century with the use of lay figures as stand-ins for live sitters (a practice that was so easy to detect in figurative painting in its day that it is analogous to a contemporary photoshop ‘fail’). In the painting Rebecca,McKenzie looked at portraiture as a tool in the study of the history of fashion, this being an important source of reliable data on the colours of fabric in a time before widespread colour photography.

Many of the surreal objects in the compositions in Giving Up The Shadows On My Face are made by her extended circle of friends - the Czech artist Pavla Dundálková, designers Michael Anastassiades and Valentina Cameranesi. McKenzie inhabits the methodologies and aesthetics of other artists (the architect De Bruyker, the designer Vionnet, the painter Frampton) in recognition of arts interconnectedness.

In the process of studying Vionnet and Frampton, the artist realised several points that these unrelated artists shared. Frampton’s work is balanced (both visually and conceptually) between the psychological drama of Surrealism and the shallow ocular preoccupation of Photorealism. His work’s detailed finish renders each object and person as a discrete sculptural entity, treating every element of the composition equally. By replicating Frampton’s work McKenzie observed that both the couture of Vionnet and the paintings of Frampton achieve absolute technical perfection, and that the perfection discreetly hides, beneath an impression of effortlessness, the complex procedures of construction and hours of labour needed to make them. These figures’ technical felicity bonded with conceptual ideas to produce interesting counterpoints to the prevailing ideas about Modernism that permeated their milieu in the early twentieth century. Frampton’s work would have been read as conservative within the climate of British art at the time, being neither abstract nor gestural. Similarly, Vionnet’s overt femininity and Neo-classicism was seen in opposition to the dominant notion that woman’s dress, to be explicitly modern, could only do so by adopting masculine tropes such as trousers and workwear. Her innovations were ‘hidden’ in the final gowns, which often appeared to have emerged from antiquity. The strict geometry came to life when activated by the natural movement and curves of the women she dressed.

Our taste and ideas about beauty and acceptability are shaped by context. McKenzie has a long-standing interest in the representation of women under Totalitarianism, as a stylistic form and as a reflector of Western capitalist conventions. She observed that in a city such as Moscow, where there is still a strong presence of Soviet era public art, being presented on a daily basis with idealised figures from an unfamiliar period and mindset, different from the kind that dominate public space through advertising and the mass media under Captialism, one feels one’s own personal desires being influenced and rerouted by their culture surroundings.

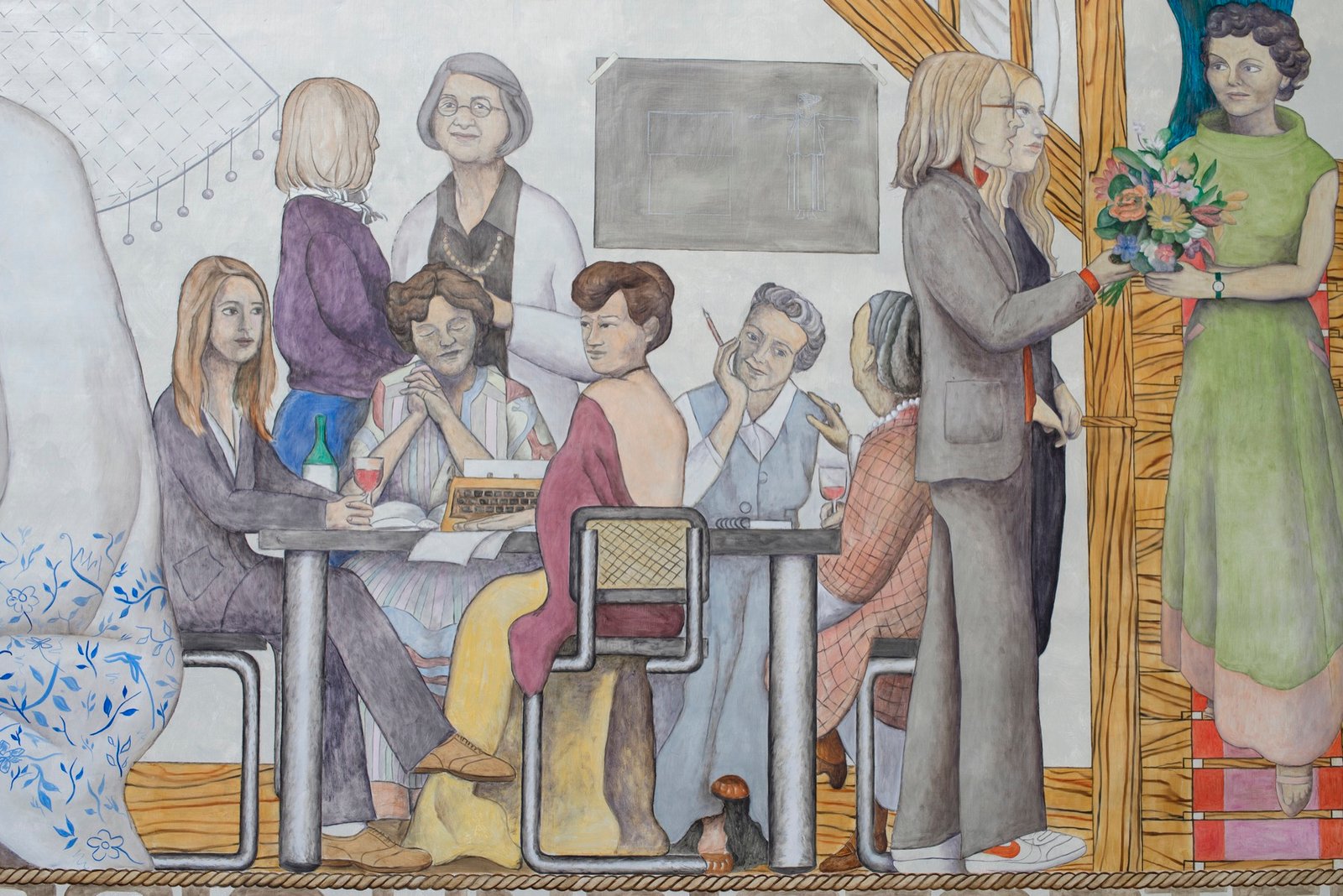

The large hidden mural that fills the central wall of the show has been staged as if just found beneath a false wall. It is a replica of the mural on display in the central reading room of the Russian State Library in Moscow. But it has been reinterpreted by the artist to have its repressive sexuality slightly loosened and to illustrate the private lives of individuals away from Soviet ideals. Couples furtively touch, a gymnast smokes and nakedness becomes nudity, counter to the de-sexualisation that Soviet culture tried to impose on the naked body. It is suggestion that defines the space between the pornographic and the erotic.

A mannequin cannot be naked, it can only be undressed. The mannequin perched on a tabletop sits undressed save for a pair of old Czech gym shoes. This is in honour of the important role shoes play in the essential narrative of pornography, grounding the blank body in a specific space and time. The tabletop quodlibet features sexually charged books. A found a copy of 1900 by Rebecca West turned out to have been collaged with the porn collection of a previous owner; in Temple Aux Miroirs, by the photographer Irina Ionesco and the writer Alain Robbe-Grillet, Ionesco’s use of her underage daughter as a photo model in the 1970s typifies debates around eroticism that remain contentious today.

The title of the exhibition is taken from the track Giving Up by electronic musician Martial Canterel and used with permission.

Lucy McKenzie

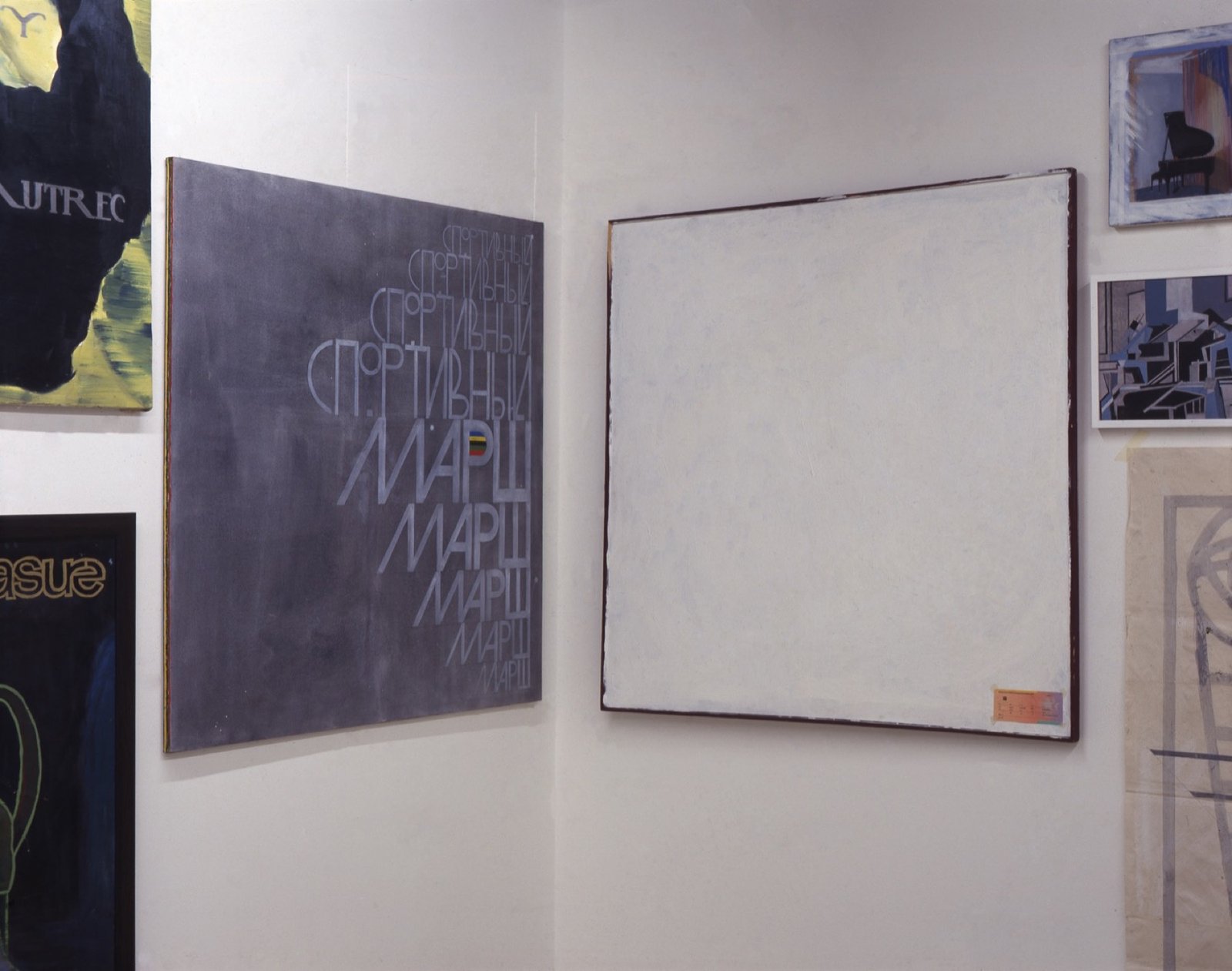

Installation view, Decemberism, Cabinet, London, 2000

Lucy McKenzie

Installation view, Buildings in Belgium, Buildings in Oil, Buildings in Silk

La Verrière, Brussels, 21 January - 26 March 2022

For “Matters of Concern | Matières à panser”, Lucy McKenzie presents her first solo show in Belgium, where she has lived and worked since 2006: a monumental installation in the form of a large-scale painting that covers the walls of LaVerrière and subtly engages the architectural setting. Inspired by history painting, allegorical narrative and, above all, the muralist tradition, McKenzie harnesses the propagandist purpose as a tool (conversely) for raising awareness. Carefully composed, peopled with objects, historical situations and figures, real and invented episodes, the scene’s decorative treat- ment masks a critique of the official, heroic history of modernity in fashion, architecture and design. McKenzie’s deliberate blend of registers, periods and figures reinforces her corrective, satirical take on an idealised narrative. As always in her work, she shows evident delight in the practice of painting, with mordant wit and a very real sense of aesthetic enjoyment. This new project freely associates critical and feminist issues with more personal, intimate concerns. As such, we may also read it as a kind of fragmented portrait of the artist, an exploratory exposition of her own interests, flash- points, esires and aspirations – her contradictions, too. In counterbalance to the painted walls are two objects made by Atelier E.B, the fashion label the artist runs with Scottish designer Beca Lipscombe. Here they present a folding paravent screen and Street Vitrine, a sculpture that acts as a flexible display case, here showing pieces from their latest collection Dash People. Between art, design, research and commerce, the duo operates as double agents between multiple spheres.

Lucy McKenzie

Installation views, Lucy McKenzie

Tate, Liverpool, 20 October - 13 March 2022

Lucy McKenzie

Installation views, Lucy McKenzie

Museum Brandhorst, Munich, 10 September 2020 - 21 February 2021

To read the in depth Cabinet Features on this show please click here